At our intentionally multi-ethnic church, a discussion has arisen from our examinations of Paul’s epistle to the Galatians. We have been interacting about the characteristics of our particular gospel-centered community, trying to describe what it is like and what defines its culture. We’ve been considering what it looks like to give the gospel precedence in our hearts and minds over our cultural customs so that there is no cultural monopoly.

At our intentionally multi-ethnic church, a discussion has arisen from our examinations of Paul’s epistle to the Galatians. We have been interacting about the characteristics of our particular gospel-centered community, trying to describe what it is like and what defines its culture. We’ve been considering what it looks like to give the gospel precedence in our hearts and minds over our cultural customs so that there is no cultural monopoly.

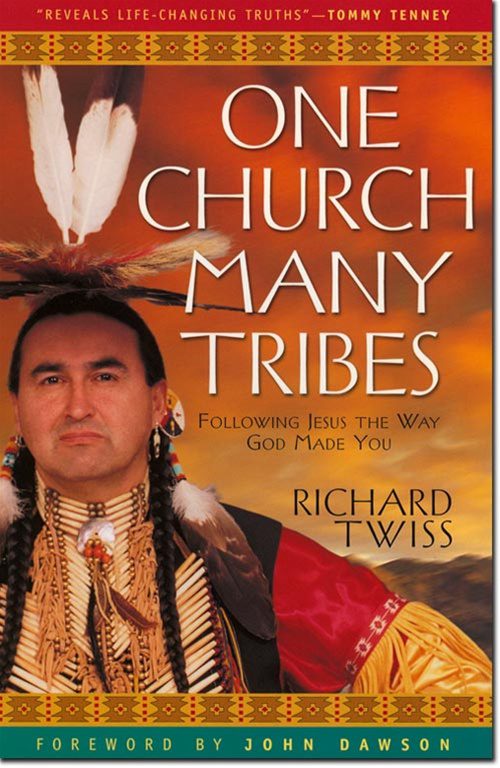

The late, great Lakota Sioux Christian leader Richard Twiss’s words on cultural hegemony are relevant here: “Because we are all so prone to be culturally egocentric, the temptation is to consider our worldview the biblical and correct one, shunning all others as unbiblical and wrong. Worse yet is our habit of judging cultural ways—songs, dances, rituals, etc.—to be sinful when there is no clear violation of Scripture” (Richard Twiss, One Church, Many Tribes: Following Jesus the Way God Made You, Regal, p. 113).

The late, great Lakota Sioux Christian leader Richard Twiss’s words on cultural hegemony are relevant here: “Because we are all so prone to be culturally egocentric, the temptation is to consider our worldview the biblical and correct one, shunning all others as unbiblical and wrong. Worse yet is our habit of judging cultural ways—songs, dances, rituals, etc.—to be sinful when there is no clear violation of Scripture” (Richard Twiss, One Church, Many Tribes: Following Jesus the Way God Made You, Regal, p. 113).

Cultural monopolies are often based on forms of cultural egocentrism. Such cultural egocentrism was present in Galatia, as the false teachers (Judaizers, as they are often called) were imposing on Gentiles regulations (circumcision laws) that were intrusions to the gospel that Paul, Barnabas and the leaders of the Jerusalem church proclaimed (we find unanimity of perspective on the gospel in the decision of the Council of Jerusalem on faith and circumcision in Acts 15). In Galatians 2, however, Paul tells us that when he, Barnabas and Peter/Cephas were in Antioch, Peter was guilty of going over to the Jewish table and abandoning fellowship with the Gentiles (with whom he had eaten in Antioch) when certain Jewish men associated with James came down to Antioch from Jerusalem. Paul called Peter on it. I believe that what had happened here was that these Jewish men embraced a form of cultural egocentrism: Jews were better than Gentiles, and such superiority was based on faith plus adherence to Jewish cultural forms and associations. Their sense of superiority won Peter over so that he sought to gain their approval, thus abandoning table fellowship with the Gentile Christians. Egocentrism has a way of building walls of division concerning who is in and who is out and causing people to seek to win the insiders’ approval. Of course, in the history of the Western world, Gentiles have often played this heinous egocentric card in their interaction with Jewish people to horrific effect. Cultural egocentrism can often lead to cultural genocide, as has been the case concerning Gentile impositions on the Jewish community in Western history and concerning Western and other cultural impositions on indigenous peoples throughout the world. Thus, we see that such cultural hegemony can work in a variety of ways.

In his letter to the Galatians, Paul, a devout Christian of Jewish heritage, challenges the Gentile Christians in Galatia not to succumb to the cultural egocentric pressures imposed on their community from the Judaizers, as had occurred in Antioch with Peter. It is not that circumcision was bad. It was fundamentally important to the preservation of the Jewish community in its history and heritage before God. Still, it was not to be imposed on the Gentile Christians, who according to Paul, were equal to the Jewish Christians through the faithfulness of Christ and faith in Christ (See for example Galatians 3:26-29).

Here are some questions our pastor posed for reflection in bringing Galatians to bear on our multi-ethnic church context followed by my responses:

What does it look like to have the gospel ‘de-mote’ our cultural customs in our minds and hearts and in our multiethnic/multicultural community? While the gospel does not demote the cultural customs of one’s people group, it does guard against those customs being enforced on others. As Richard Twiss reminds us, we must guard against thinking of our cultural forms as the only way in which the gospel can be expressed. By realizing that the Bible does not endorse or condemn a given culture as such, we can move forward with greater freedom while remaining confident that God is faithful to contextualize the good news in our cultural context without the good news being enslaved to that context.

What does this gospel centered community look like? What are its mannerisms? In place of cultural egocentrism, we need to celebrate cultural humility and inquisitiveness. In this context, humility entails not promoting our distinctive cultural forms as absolute and others as relative. In this domain, inquisitiveness entails seeking to discern how God makes contact with us in and through our own cultural forms as well as seeking to learn of how God works in other cultural contexts in raising up faithful witnesses to the good news of Jesus Christ in various cultural forms.

How do we get there? Getting there requires that we learn to “talk story” with one another of diverse cultural contexts in a given local church and beyond. Of course, this will entail that we move beyond homogeneous church models that focus exclusively on one ethnic group of people to the exclusion of others. We need to learn to celebrate one another’s cultures in a given locale while always shining the light of Scripture on each of our cultural heritages to make sure that there is no clear violation of Scripture, in keeping with the intent of the quotation above from Richard Twiss. Of course, this is often easier said than done. “Talking story,”referred to above, a Hawaiian cultural expression, requires vulnerability and transparency, which requires time and energy and good listening skills, as we share with one another how it is we see the good news of Jesus Christ taking root in our distinctive cultural contexts in unique and particular ways. As with First Nations talking circles, which make space for everyone to share as equals, space must be cultivated for everyone’s voice to be heard as we seek to bring Scripture to bear on our respective cultural heritages in service to the community of faith. Only then will we move beyond monolithic to multiethnic expressions as the one body of Christ.

This piece is cross-posted at The Institute for the Theology of Culture: New Wine, New Wineskins and at The Christian Post.